Image description:

Picture with a slightly run-down looking church’s front door on the right side of the picture, and on the left a section of the church’s wall and a graffiti-covered dumpster in front of it.

On the wall is graffitied a 4x4 table with the columns labeled from left to right “M”, “F”, “N” and “PL” – for the masculine, feminine, neuter and plural forms. The rows are labeled from top to bottom “nom”, “akk”, “dat”, “gen” for the nominative, accusative, dative and genetive cases. The corresponding definite articles are written out in the table each in its own spot (I hope screen readers don’t barf with tables):

| M | F | N | PL | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| NOM | DER | DIE | DAS | DIE |

| AKK | DEN | DIE | DAS | DIE |

| DAT | DEM | DER | DEM | DEN |

| GEN | DES | DER | DES | DER |

Just in…case… you need it.

There’s a school on the other side of the road

Just in case anyone wants to learn the German cases from a table in an image description: Dativ Plural should be DEN.

Argh, I was squinting at the text and just went “… I think it was dem? I’m pretty sure it’s dem” As I said in another comment, grammar has never been my strong suit (in any language)

To be honest, I have no idea how anyone can memorise that. As a native speaker you hardly ever really think about it, you just know. But looking at the table it just seems like complete chaos, even to me.

how anyone can memorise that

Use it in a 1000 sentences each.

I barely speak German, but I do speak Polish where there are 7 cases, and it’s just “how things are”. Sometimes you stop to think about why, and it feels kind of surprising.

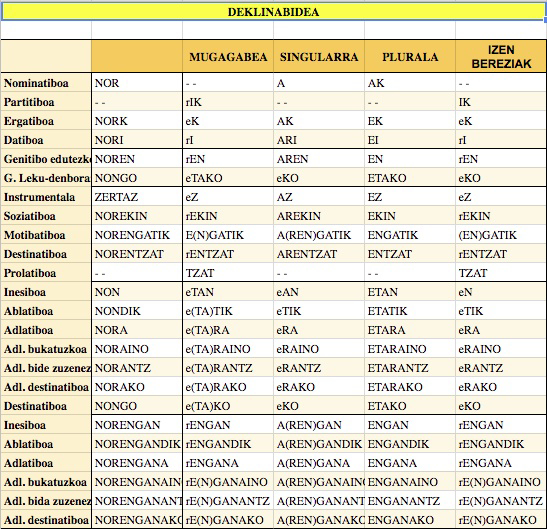

Then, I also speak¹ Basque, which has 17 cases… let me illustrate:

A Basque noun is inflected in 17 different ways for case, multiplied by 4 ways for its definiteness and number. These first 68 forms are further modified based on other parts of the sentence, which in turn are inflected for the noun again.

…that’s the easy part, before verb conjugation:

(non-exhaustive table for just the regular helper verbs)

¹ “speak” as in only having to look up the conjugation tables from time to time.

It really is. Once we got past nominative and accusative in school (which were hard enough coming from English which has no gender), and suddenly this chart was busted out, I realized German was always going to be a guessing game for me. I can only hope the meaning is clear enough with completely wrong genders and word endings. I find I do better hearing whole phrases repeatedly than learning word by word, but seeing this helps with knowing why a phrase is worded a certain way.

At least the graffiti artist made the right case for den homeless people learning German in the street.

“for die homeless people” :)

(Insert obvious allusion to “die, Bart, die” scene here.)

Wer deutsch spricht kann kein schlechter Mensch sein.

Nicht laminiert.

Impressum fehlt.

Schriftart nicht DIN-gerecht.

Weder Fließentisch noch Blattsalatschüssel.

*Fliesentisch!!!11

Die Fälle haben die falsche Reihenfolge, aaaaahhhhhh!

Nom, Gen, Dat, Akk.

Musste ich aber noch mal googlen, weil ich erst Nominativ und Akkusativ in der Reihenfolge vertauscht habe.

Exakt

Es gibt wohl einige Länder, die den Akkusativ zumindest in der Lateindidaktik nach den Nominativ setzen. Frag mich nicht, welche bahnbrechenden pädagogischen Erkenntnisse dazu geführt haben – macht in internationalen Lateinforen immer mal wieder etwas Konfusion, welches nun genau der “zweite Fall” ist…

!unexcpectedmontypython

„Romanes eunt domus“, what‘s that supposed to mean?

Romani domum ite — Romans go home.

“People called Romanes they go the house”?

Gute Bildbedschreibung. Als der Maler würde ich aber die Spalten × Reihen umtauschen.

Es würde mich trotzdem verwirren 😅 Grammatik ist nicht meine Stärke

Edit: und danke

Muss das in deutsche Grundschulen gelehrt werden oder nur bei DAF?

Weiss nicht, ich bin finnisch 😅

Natürlich wird das in Schulen gelehrt. Ich bin mir aber nicht mehr sicher, ob das in der Grundschule dran kam oder erst in der 5./6. Klasse.

Ernst?! Deklination schaffen Kinder als teil der Muttersprache schon ver der Schule, oder? In Tschechien werden die 7 Fälle gründlich in der 3. Klasse gelehrt, denn sie für i/y-Rechtschreibung wichtig sind.

Hängt von der Muttersprache ab – die meisten deutschen Dialekte haben nur noch 2 – 3 Fälle, und ein Bekannter hat mir erzählt, dass schon vor 30 Jahren an seiner Grundschule ein Integrationsprojekt für Nicht-Muttersprachler gescheitert ist – weil sie nicht genug Kinder mit Deutsch als Muttersprache gefunden haben.

die meisten deutschen Dialekte haben nur noch 2 – 3 Fälle

Das ist etwas neues für mich. Auf meinem Gymnasium wurden Präpositionen mit dem 2., 3., 4. und 3./4. Fall gelehrt. (Die lateinische Namen werden hier nicht verwendet, denn wir 7 Fälle haben und das wäre zu viel.) Das heißt aber nicht, dass ich die merke - ich benutze meistens das ~70% richtige Hilfsmittel von “Modulo 4”: 1→1, 2→2, 3→3, 4→4, 5→1, 6→2, 7→3.

Na ja – wahrscheinlich wurde auf dem Gymnasium ja auch Hochdeutsch gelehrt und nicht Hessisch/Schwäbisch/Sächsisch/Fränkisch/Bayerisch usw. Und Hochdeutsch hat noch 4 Fälle, auch wenn der Dativ dem Genitiv sein Tod ist und der Genitiv in einer Generation wahrscheinlich ganz aus dem Hochdeutschen verschwinden wird. (“dem X sein Z”/“der Y ihr Z” ist neben “Z von X/Y” ein häufiger umgangssprachlicher bzw. dialektaler Genitiversatz)

Modulo 4 ist klasse — wobei ich glaube, dass wir da, wo Tschechisch den 6. oder 7. Fall nutzt, Präpositionen nutzen.

Bin mir ziemlich sicher, dass sowohl als auch. Wer-Fall, Wessen-fall, Wem-fall und Wen-fall in der Grundschule, Nominativ, Genitiv, Dativ und Akkusativ in der weiterführenden. Und/Oder 1., 2., 3. und 4. Fall in beiden.

Wobei das von Bundesland zu Bundesland unterschiedlich sein kann. Es lebe der Föderalismus!

Last row’s description says DEN instead of GEN ;)

Oh whoops, brain fart 😀

PL DIE DIE

Hmm

Thanks for taking the time to type it out, I couldn’t read the letters on the picture as my phone is too small.

Now we need a table with the adjective endings and which movement prepositions go with what (Ich gehe nach/ins/auf/zu)