I raise my tube

Only for a moment

And the sample’s gone

All my dreams

Flee before my eyes

Like Ingenuity

Dust in the wind

All they are is

Dust in the wind

Same old song

One more grain of basalt

in an endless flow

All we drill

crumbles to the ground

Though we refuse to see

Dust in the wind

All we are is

Dust in the wind

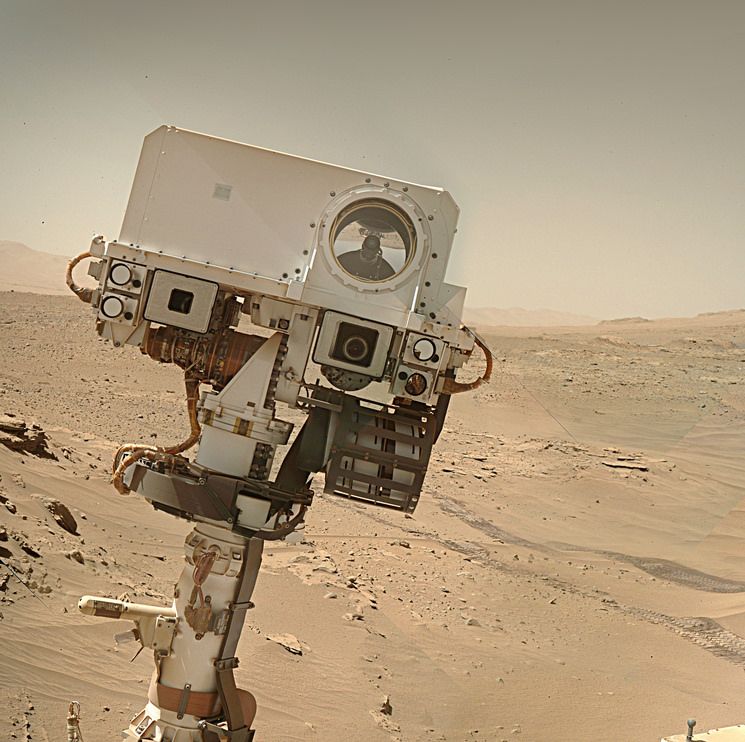

The coring seems to have been successful on this occasion.

For reference, the abrasion patch on the right is the latest one (#35), the fourth taken here at Witch Hazel Hill. I do hope that forthcoming mission updates will share more, at least qualitatively, about the drill data for all the recent coring attempts. It would be pretty illuminating to know which rocks have required the most time and force, given the sampling failures and unpredictable nature of the geology here.