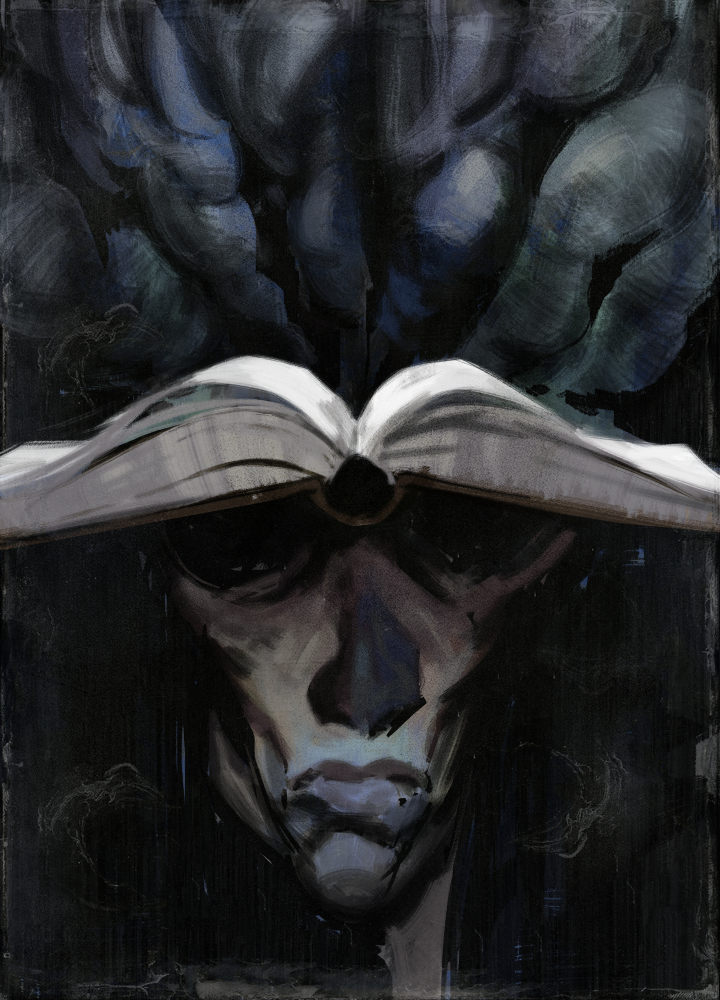

Closer to home, desperation even might push us to “envision real utopias” in any marginal glimmer of communality: the noble Wikipedia editor, the worker cooperative competing on the global market, the sharing of food at the protest camp, the persistence of the public library despite the endless assault of privatization, the urban garden tended by the six-figure NGO executive, the sharing of cigarettes near the dumpsters behind the kitchen, or simply the commonplace care work that knits us to family and friends. To imagine that such things are somehow the germ of communism would be a joke if it was not so tragic. Like someone who believes that the window projected onto the wall is the real thing. The bleak reality is that none of us have ever seen even the dimmest glimmer of a communist world—at most we have witnessed a few of those weightless moments when many people realize at once that our world can, in fact, be broken. Ultimately, these are nothing but glowing images best seen from a distance. Reach out to touch them and there is no depth. Just work, survival, desperation. Just the drywall, off-white.

[…]

Below, we therefore offer a practical fiction rooted in a negative critique. Throughout, we will counterpose our account to what we think are common errors that plague the political imaginary while emphasizing the inherent unknowability and dynamic cultural efflorescence of a communist world. While the contrast between practical fiction and negative critique may seem paradoxical—an anti-utopian utopia—such a procedure is the nature of scientific inquiry. As in any scientific inquiry, the models that we pose here are ultimately makeshift. But, without any ability to directly observe or experiment, a certain degree of fictive rigor is essential in their construction. Imagination must be subject to at least a minimum level of real constraints. Among these are the “social forces” and “political, class forces” that have been produced by the course of history, which Lenin emphasizes. In addition, we stress here the equally prominent role of “productive forces” as concrete sites of social power, irreducible to their technical characteristics. In fact, we would argue that the failure of nearly every utopian vision on offer today manifests most strongly in their treatment of the question of production, which is either ignored entirely, presumed to be a purely technical-ecological matter best left to the experts, or viewed as so thoroughly subordinated to capitalist logics that prevailing agricultural and industrial practices must be uniformly and fundamentally replaced—with what, exactly, it is rarely clear, though gestures are often made in the direction of local autarky. Questions of locality and the precise process of production will therefore serve as lenses bringing focus to our own anti-utopian utopia or, more simply, our contribution to the science fiction of communism.